There is a special kind of calmness that comes with sitting by a Himalayan river. The bank is often littered with pebbles, smooth and warm in the sunshine; the water is icy-cold and invigorating, and the sound of the river — nature’s white noise — has the capacity to drown even the most niggling thoughts. In these moments, it is evident why so many spiritual traditions ascribe sacred value to rivers: They are the lifelines of our planet, bringers of freshwater, breeders of life, and reminders of the ever-changing and wonderful impermanence of life.

Rivers are crucial to the harmonious running of Earth’s ecosystem, and yet, there are relatively few studies on freshwater ecosystems in India and around the world. As a result, freshwater species (of fish in particular) do not receive much attention, even though India’s staggering riverine systems are brimming with biodiversity.

Among the many species that inhabit the country’s rivers, is the mahseer, a member of the carp family known for its agility and large size. India has about 19 species of mahseer — belonging to the Naziritor, Neolissocheilus, and Tor genera. Different mahseer are found across the country, from Himalayan streams to rivers in the Deccan Plateau, though taxonomical studies are still incomplete, and there are species yet to be classified. Of the ones we know, the golden mahseer (Tor putitora) is the largest, with records of fish measuring 3 m and 54 kilos! It is sometimes called the “tiger of the water”, for its vigour, golden colour, and athletic abilities.

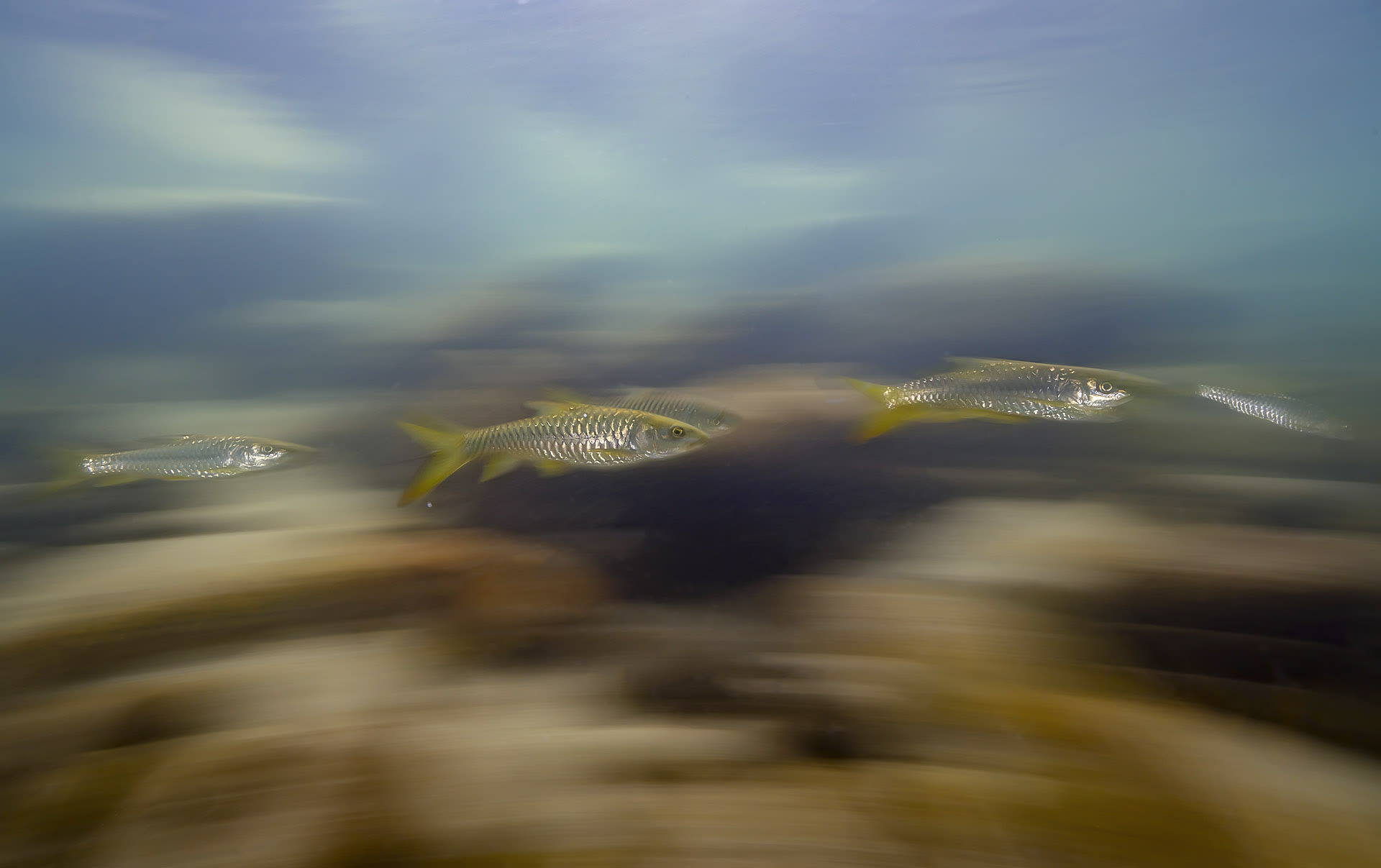

Though golden mahseers are found in rivers and streams from the Euphrates and Tigris rivers in Iraq to waterbodies in Southeast Asia, “the Indian Himalayan rivers are thought to be the real distribution,” says Dr Vidyadhar Atkore, Senior Coordinator of WWF India, who has spent many years studying the species and its habitat. The golden mahseer is found in Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and the northeastern states of Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Sikkim, Tripura, and Manipur. These photos were taken in the Ramganga river, which originates in the Dudhatoli hills of Uttarakhand state, flows through Corbett National Park, and onward to Uttar Pradesh.

Golden mahseer spend much of their lives in deep stretches of rivers and mountain pools, where food is plentiful. Twice a year, however, adult males and females migrate to breed and feed at higher altitudes. The fish’s ability to swim upstream, against gravity, and over rocky boulders and streams, is another reason it is called the “tiger” of the water. “They can easily leap over small to medium-sized rocks and boulders,” says Dr Atkore, adding that the migration happens twice a year depending upon altitude. “Once during early monsoon (June-August) and post-monsoon (September-October).”

The fish swim upstream to find waters suitable for their young: shallow in depth, with slow water currents, and high oxygenation levels. They prefer waters that are “rich in stream substrate composition,” explains Dr Atkore, “where young can find abundant food, such as insect larvae”. Females tend to favour confluences of tributaries, and often lay their eggs at night, around submerged gravel. While the female lays the eggs, the male makes brisk movements of the caudal (tail) region, fertilising the spawn with his milt (aka fish semen). Soon after, the adults return to deeper pools downstream.

Golden mahseer are large, agile and lively, which accounts for why the species is so popular with sport fishing enthusiasts who wait to catch them in shallow waters with rod and line. Uttarakhand has several angling camps and resorts, where catch-and-release fishing is practised with great enthusiasm. “Catch-and-release programmes seem to sustain local employment,” says Dr Atkore, which is an important part of conservation, “but it also injures fish, a fact that that usually goes unnoticed or at least unstudied”.

However, there are bigger threats to the mahseer than angling communities. In recent years, the species has been hunted in alarming ways: using dynamite, poison, even electrocution. These practices still exist in Uttarakhand and other states. Habitat loss is another cause for concern. Hydrological projects hamper the golden mahseer’s ability to migrate, as the species requires connectivity in a river system. “Ramganga Dam and several other dams in Himalayan states have posed a hindrance to the natural migratory pattern of this species,” explains Dr Atkore. “This has fragmented their population both above and below the dams, and restricted genetic exchange.”

There are short-term and long-term consequences to the building of dams and reservoirs, says Dr Atkore. These waterbodies are often stocked with non-native fish, which further depletes local vegetation, flora, and fauna, all of which impacts the golden mahseer. “We need to stock reservoirs with native species, engage local communities to fish the non-native species, and construct passages at each dam to allow fish migration,” says Dr Atkore. He also suggests other forms of ecotourism, such as rafting, which utilise the tourism potential of Himalayan states, without harming the fish.

Dr Atkore believes that policy-level change is the need of the hour. “If both state and central government accord it special status i.e. Schedule-I in the Wildlife Protection Act (1972), this will help sustain the population in the future and curb illegal and destructive fishing practices.” Additionally, restoring mahseer habitat, protecting migratory routes, rejecting new dams, and creating conservation reserves to safeguard their genetic stocks, would also be helpful. “Local communities, as well as some of the temple authorities (small and large) in Uttarakhand, have been conserving the mahseer’s habitat and population for many decades now,” says Dr Atkore. “Acknowledging and encouraging their efforts might help sustain the population of this majestic species in their native habitat.”

Ultimately, the status of rivers in India, and around the world, reveals a deeper crisis: the human race’s disconnect with natural habitats. Somewhere along the way, we seem to have forgotten that we are an extension of our ecosystems, and the health of humanity is intimately connected to the vitality of the home planet. As the pioneering Japanese conservationist, Tanaka Shozo once eloquently stated, “The care of rivers is not a question of rivers, but of the human heart”.