The beauty of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands creates an impression of pristineness or being “untouched”. On the contrary, this archipelago in the Indian Ocean has a rich cultural history, shaped by the lives of its residents at various points of human evolution and civilisation.

The islands form an arc between the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea, connecting Myanmar in the north and Sumatra to the south. During the 65 million or so years of their existence (dating back to the Cenozoic era) these Islands have been a naturally isolated laboratory for incredible evolution and change.

Politically, the islands changed administrative hands three times (British, Japanese, and Danish) between the mid-1700s and being handed over to India in 1950. Rewind to 1014 AD when Rajendra Chola of the Chola Empire used these islands as a naval base to conduct expeditions planned against the Sriwijaya Empire (Indonesia today). The oldest residents of these islands are, of course, the indigenous people who have lived here for 30,000-60,000 years.

Presently a union territory, commercial fishing port, tourist hotspot, and tri-defence base for the Indian Armed Forces, this precious, emerald archipelago consists of 572 islands, with two volcanoes and numerous endemic animals and plants. Each island is thick with tropical evergreen forests, transitioning into vast contiguous mangroves or tall littoral forests. The coasts have dazzling white beaches gradually sloping into an ocean floor carpeted with coral reefs that can be seen from the sky.

For the 21st-century traveller, 1,600 kilometres into the sea from mainland India may not seem too remote given the air connectivity to this archipelago. When the globally renowned ocean explorer and co-inventor of scuba diving, Jacques Cousteau, visited the Andaman Islands in 1989 he called them “the invisible islands”. He saw an underwater paradise teeming with marine life, from large schools of fish to magnificent coralline formations. This is how the coral reefs are even today.

A moray eel and puffer fish jointly take cover under a massive Porites coral boulder. The Porites group of corals are one of the main framework builders for reefs in the Andaman Islands. They are some of the longest living (at least 200-300 years) and largest (up to 6-7 metres tall) stony corals in the world. They provide other corals, fishes, and millions of reef denizens a foundation to colonise and grow further in every dimension, including boring through their own calcium walls. Although Porites boulders can dwarf a diver by size and age easily, they are extremely slow growing (on average 1-2 cm a year) and a significant setback to the health of a reef if lost.

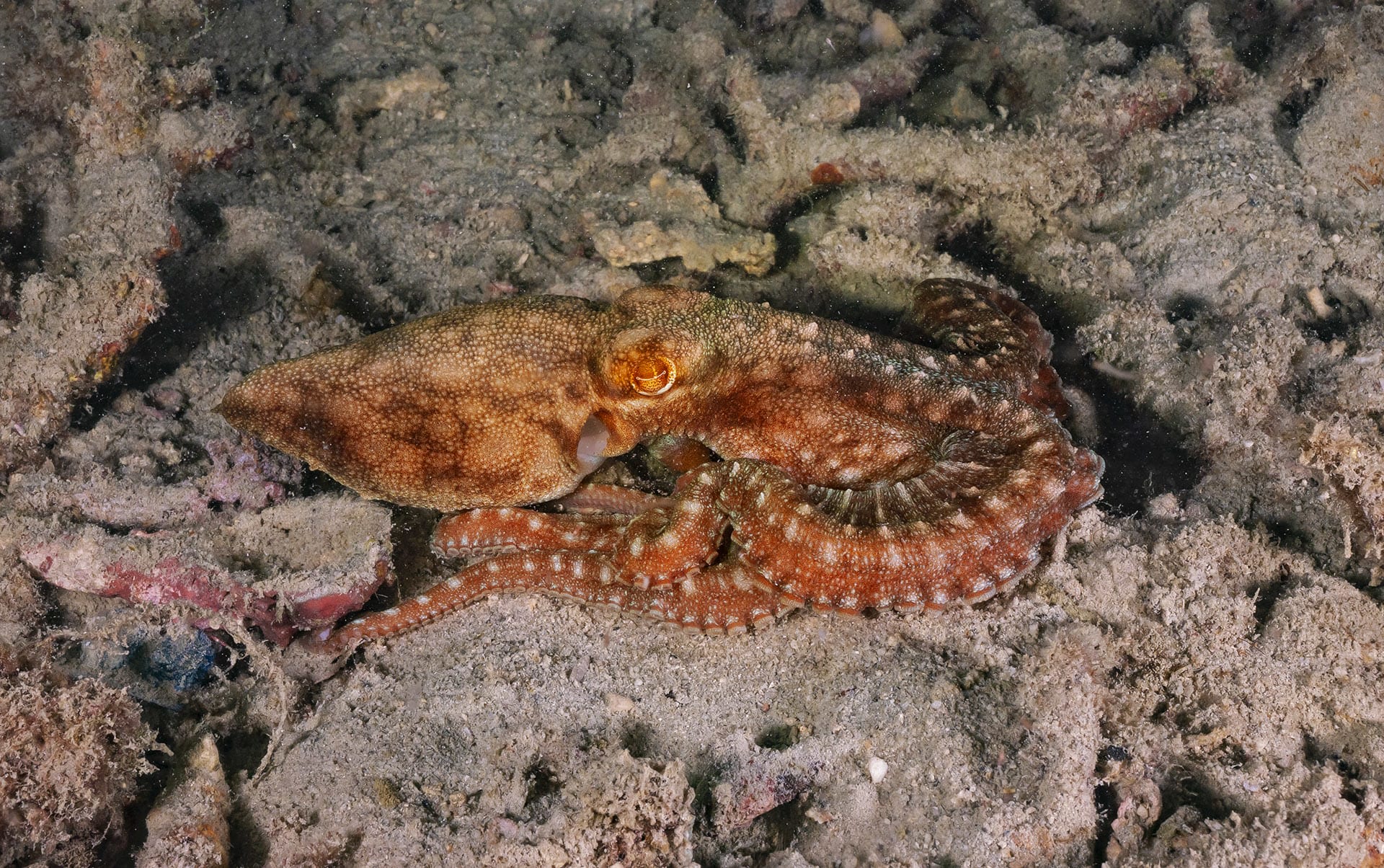

Like coral reefs globally, reefs in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are living through the impacts of 21st-century climate change. Repeated instances of ocean warming, especially the devastating coral bleaching episode in 2010, caused significant damage to coral health on these islands and inadvertently the ecosystem built on it over centuries. Shallow coral reefs were hit the most as is evident from the coral rubble that can still be seen a decade later. However, there is enough reason to hope for a good recovery with new corals growing and surviving corals regaining health. Coral rubble is turning out to be an interesting habitat to observe marine life as it is a space for small critters and juvenile animals to hide. From hunting octopuses and cuttlefishes to carefully hidden scorpionfishes, and flatheads, there is plenty to see even in reefs where corals are young or still in recovery.

Coral reefs as ecosystems can have smaller ecosystems within them. Feather stars (Crinoidea) are close relatives of sea stars, urchins, and sea cucumbers. They are radially symmetrical animals with numerous sticky, feathery arms used to trap plankton from the water. But feather stars often do not live alone. They provide smaller animals with temporary or permanent shelter from predators and currents. Here we see a crinoid shrimp tightrope walking on a feather star arm beautifully blending in with the colour of its host. As soon as a predator approaches, the shrimp will vanish in the maze of sticky feathers that few would dare meddle with.

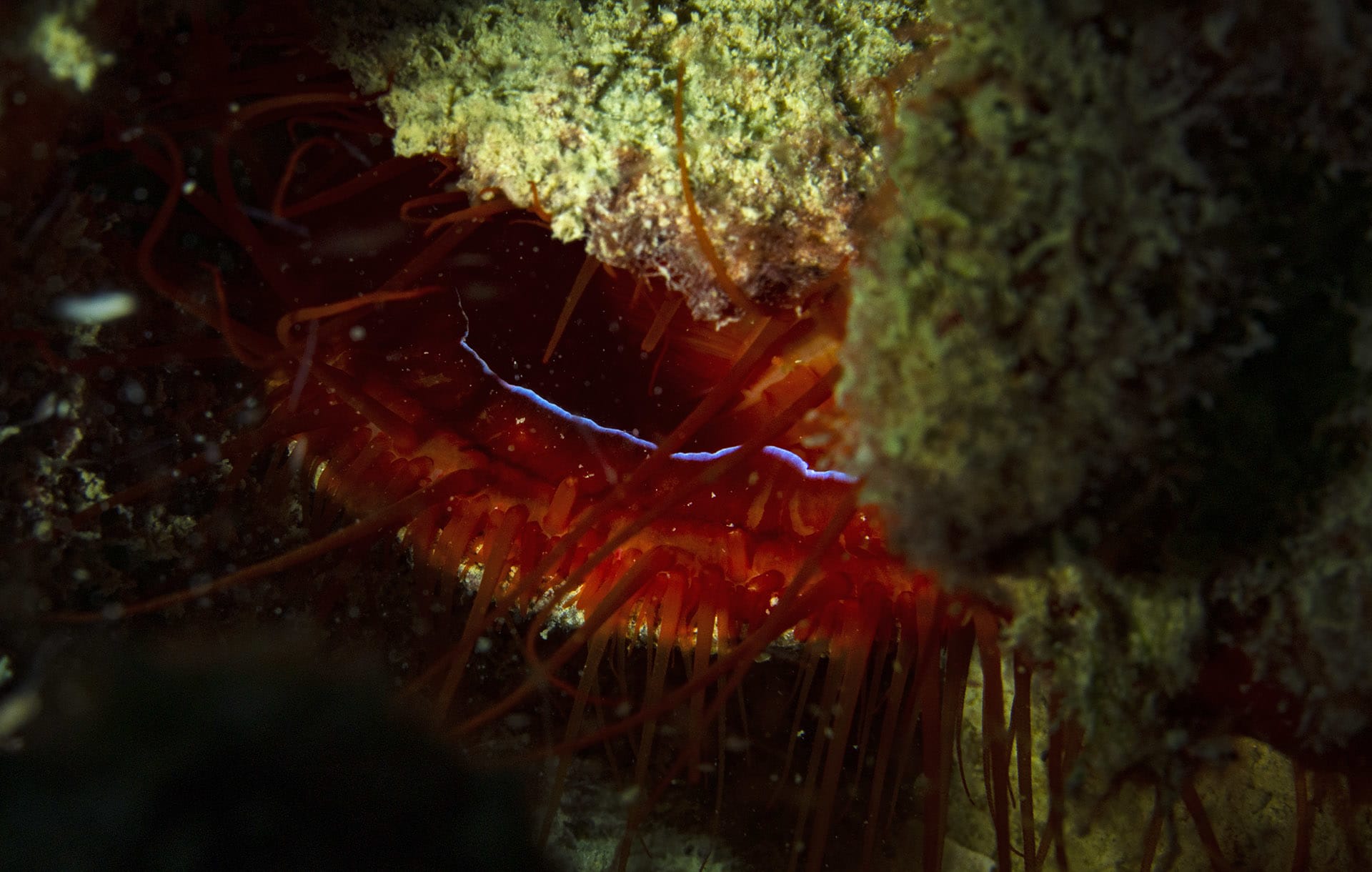

Like true treasure, much of the bizarre marine life in the shallows of the Andamans is well hidden. By boring into calcium walls of coral rocks, electric clams (Ctenoides ales) are practically embedded into the shaded slopes and caves of boulders. They are exciting to observe because of the electric displays, seen at the outer edges of the entrance of their shells, which are a potential defence mechanism. This pulsating light is often assumed to be a result of bioluminescence. Instead, using evolutionary technology electric clams produce this “electricity” when ambient light falls on highly reflective silica nanospheres lining the mantle.

Research has shown that the archipelago has around 1,439 species of fishes belonging to 165 families. While this number is staggering, what is more incredible is being able to observe this rich diversity in action in its natural habitat. Of the thousands of species, there are herbivores, carnivores, those that feed only on corals, those built exclusively to feed on plankton, and some who have designated dining areas on the reef. There are species that prefer to hunt for invertebrates in the sand, while others that are most active at night. Some species school together, others maintain lone territories, still others prefer cosying up with shrimp in burrows. Coral reefs in the Andaman and Nicobar islands are a perfect example of underwater metropolises busy with fish life from the surface to the sea bed, from the edge of the beach, all the way to the deep blue.

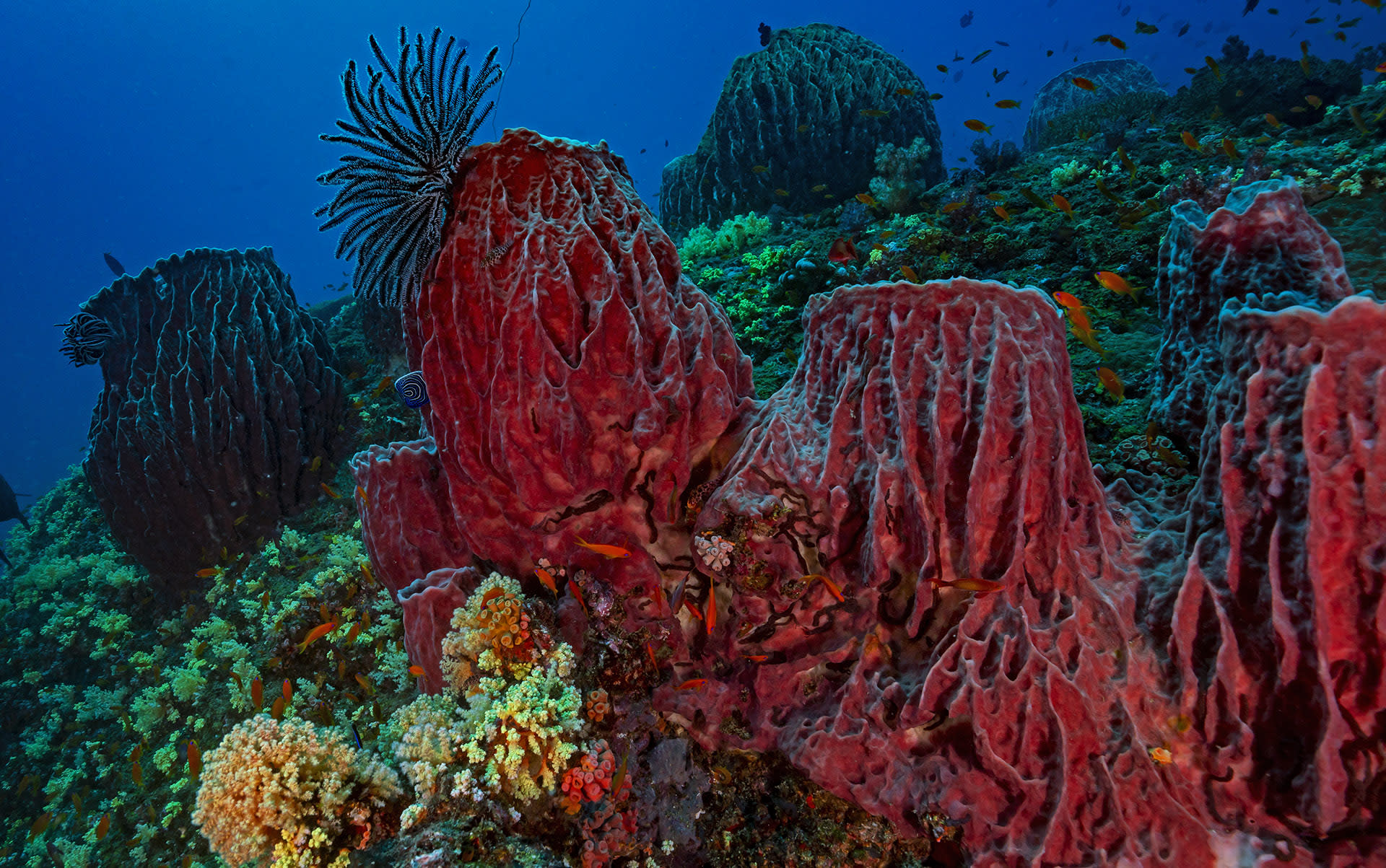

Diving into the deeper realms of the Andamans can be haunting and magnificent in equal measure. Even on days when the water is crystal clear, some reefs only come into view after descending at least 20-25 metres. One can expect to find enormous pinnacles, ledges, gorges, valleys, caves and massive tables emerging from the bottom of the sea. However, nothing prepares you for the overwhelming experience of swimming between the soft coral gardens, towering barrel sponges, and gracefully swaying sea fans while many thousands of fishes swim past.

Coral reefs in the Andaman Islands are truly special, but not because of the presence of any particular large or small charismatic animal that has to be ticked off a checklist. The water is not always crystal clear and underwater currents can be challenging. Diving or snorkelling in shallow coral reefs are like long walks in the forest, with ample time to look under every rock, stalk, and pillar for tiny invertebrates. Spending time in the deeper realms of the Andamans can make you feel small and remind you that you are a part of something bigger in this world. And, when not focussed on a single creature or species, you may find yourself hypnotised by the entire ensemble of life coming together before your eyes — that is the Andaman effect.