I inch my way down the narrow crevice, crouching to avoid the jagged edges of the limestone ceiling that hangs low over my head. In the inky darkness I have descended into, I peer around trying to discern some detail on the walls around me. I turn my head gingerly, and my head-torch lights up a spray of shimmering gold on powder white columns. I catch my breath as the ceiling gleams above me.

We are in one of Meghalaya’s smaller limestone caves, part of the subterranean world that lies underneath the region’s legendary green valleys and azure rivers. I am with wildlife photographer Dhritiman Mukherjee and a team of filmmakers on an exploration of the cave systems of Meghalaya, and the life they hold. While the caves occurring across the Garo, Khasi and Jaintia hills are typically limestone caves, Meghalaya also has sandstone caves like the spectacular, 24.5 kilometre Krem Puri, currently the world’s longest known sandstone cave. Our expedition, primarily in the East Jaintia Hills, involves exploring caves like Krem Chympe, Krem Umladaw and other unnamed, previously unexplored caves in the region. This cave is the first in a series we are exploring, a lesser-known, unnamed cave near Lumsnang in the East Jaintia Hills. Less than an hour ago, we trekked down a narrow, slippery path through dense bamboo thickets to reach a rocky overhang of limestone with a narrow opening at the bottom. Barely larger than a slit, I would have to curl myself up into a ball to enter, almost like a porcupine. In fact, it was a porcupine that had first led our local guide to this outcrop leading to the discovery of this particular krem, or cave in Khasi.

After a deep breath and contortion tricks that my gymnastics teacher from school would have been proud of, I crawl through the narrow entrance. Inside, it is another world.

The wealth of caves found in Meghalaya is unlike any other known karst (or limestone-dominated landscape) in India. What makes Meghalaya special is a combination of factors — a hilly plateau with elevations of over 1000m, a landscape rich in limestone, and an abundance of rainfall during the monsoon, among the highest recorded in the world. Fragile and mysterious, these subterranean habitats are formed by an extremely slow process of erosion by water — the wearing away of limestone or calcium carbonate bedrock over millions of years. Known as solution caves, these caverns typically form in sheets of solid limestone found below the surface like the caves that we explored near Lumsnang. In some cases, solution caves are also formed in other sedimentary rock strata that are soluble.

The process of cave formation is fascinating. When rainwater mixes with atmospheric carbon dioxide and other gases in the soil, it forms a weak acidic solution. Either in the form of underground rivers or as groundwater, this mildly acidic water dissolves calcite, the predominant mineral that occurs in limestone, to gradually carve out large cavities and often, complex cave systems.

As acidic water drips through the cracks and deep crevices already forming, the cavities widen. Water continues to seep through the rock strata till it reaches a layer that is saturated with water. Here it stagnates to form pools, and then starts flowing horizontally, to create the spectacular horizontal caves that dominate the region. Studies show that it takes over 100,000 years for the cavities to grow wide enough to hold a human.

There is a surreal beauty to caves once the veil of darkness is lifted. Often hidden from human eyes in difficult-to-reach locations, witnessing them involves braving slippery slopes, belly-crawling at times through narrow passages, and wading or swimming through icy-cold, crystal clear rivers or pools of water. In river caves where there is flowing water, like the stunning Krem Chympe, we spent days exploring, water also creates stunning rimstone dams or gours. Pictured here is one of the rarer formations, that looks like a lotus, and creating waterfalls that cascade into turquoise subterranean pools.

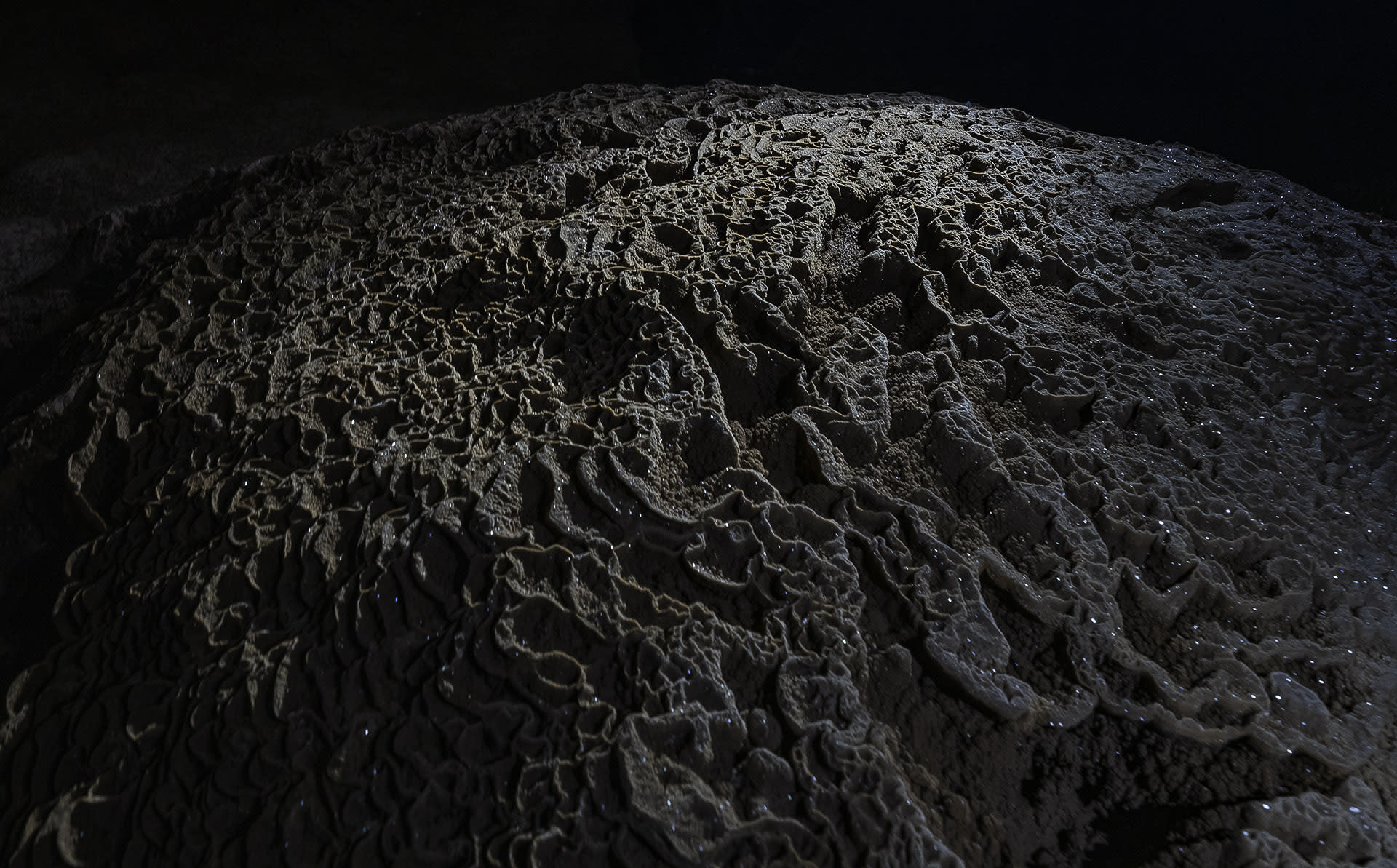

The effects of the slow action of water are everywhere, fluid movement captured in mineral deposits. Mesmerising and hypnotising, formations called speleotherms are all around us as we explore different caves. Their textures and shapes are determined by whether the acidic water has dripped, seeped, condensed, flowed, or formed ponds. After the process of erosion, as the water continues to seep in into the slowly-forming caves, it often deposits the minerals that it carries, embellishing the cave. Flowing and dripping water creates stunning patterns and formations. Cave minerals include calcite and other carbonate minerals — calcite sometimes accumulates as calcite crystals that practically glitter like jewels (above) when they catch the light.

In relict caves or passages that usually do not have running water, you could find yourself surrounded by incredible formations of all shapes and sizes. These structures have literally been formed drop by slow drop (top left). Straws (above left) are thin formations that resemble drinking straws. Nearly all stalactites, formations that grow downwards from the roof, start out as straws, developing and thickening over the years as the solution runs down the outer surface. Stalactites also take the form of draperies or curtains (above right). Flowstones (top right) are created when running water leaves behind a thick film of calcite on any surface, sometimes ending in a fringe of stalactites.

Stalagmites grow upwards from the cave floor, usually created by the water droplets that drip from stalactites. Occasionally, stalactites growing down and stalagmites growing upwards meet at some point, to ever so slowly form a rock-hard column that starts small (left) and sometimes growing into stunning, large pillars (right).

The caves hold many delightful secrets, not always visual. If you gently tap some of the stalactites and stalagmites in some of the dry caves, you will discover that they produce delightful and varied notes, creating a tune that reverberates in the eerie silence. Video: Biont

India’s deepest-known shaft cave, Krem Umladaw is a vertical sink with barely any calcite formations, characterised by dramatic, steep plunges and fossil-studded rocks and passages. The arduous exploration of this cave is not for the weak-hearted. For those willing to brave the plunge, however, it is like descending into a time capsule, an archive of millions of years gone by. Dating back to the Eocene Epoch, 56 million to 34 million years ago, the cave systems in Meghalaya hold some amazing records of life frozen in stone. Embedded in the limestone are fossilised cross-sections of shelled marine creatures, predominantly molluscs (above left), and foraminifera, a marine protozoa (above right). The occurrence of these fossils of marine creatures in landlocked Meghalaya might give credence to the theory that millions of years ago, Meghalaya was possibly an ocean bed. Photo: Divya Candade (above right)

Interestingly, these dark caverns are also habitats for incredible and surprising cave life. In the most unexpected places, deep inside chambers or in the passages, we found insects, frogs, fish, spiders, and crabs. Creatures like this water scorpion have survived in this world of permanent darkness. Caves and the life they sustain are extremely vulnerable, and activities like mining, quarrying and dumping of waste can destroy large cave systems in a largely unnoticed and silent manner, in the process wiping out rare subterranean habitats and geological treasures.